THE SEQUENCE OF CARDIOPULMONARY RESUSCITATION (CPR)

When a casualty has no pulse and is not breathing, you must combine artificial ventilation with chest compression.. This is the sequence known as CPR.

You must, if alone, call for help before you star CPR. With a helper – ideally, a second. First Aider – the situation become easier. In every case, you must persevere with resuscitation attempts until either a pulse returns, professional help arrives and takes over, or physical exhaustion forces you to stop.

FOR ONE FIRST AIDER

1. Immediately dial 999 for an ambulance.

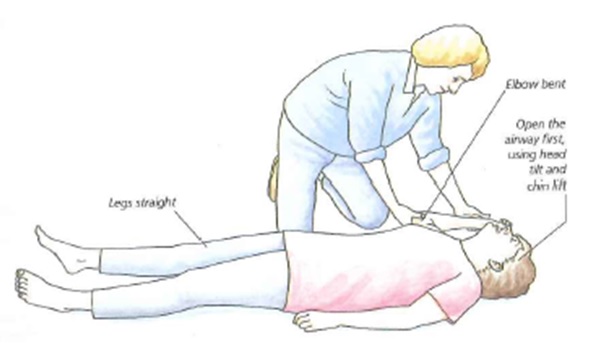

2. Open the casualty’s airway by tilting the head and lifting the chin, and give two breaths of artificial ventilation.

3. Move your hands to the casualty’s chest, and give 15 chest compressions.

4. Return to the head and give two more ventilation.

5. Give 15 further compressions.

6. Continue to give two ventilations every 15 compressions until professional help arrives.

It is very unlikely that you will be rewarded by the heart re-starting before expert assistance is given. Do not interrupt CPR to make pulse checks unless there is any sign of a retuning circulation. With a pulse confirmed, check breathing and, if it is still absent, continue with artificial ventilation. Please check the pulse after every 10 breaths, and be prepared to re-start chest compressions if it disappears. If the casualty start to breathe unaided, place him or her in the recovery position. Re-check breathing and pulse every three minutes.

FOR TWO FIRST AIDERS

One person should go to summon help while the other immediately starts CPR. Then, either puoceed as above, each person taking it in turn, or while one of you gives chest compressions, the other can give one breath of artificial ventilation after every five compressions.

Pause to ensure that the casualty’s chest rises, but do not wait for the chest to fall before continuing with chest compression.

MAKING A DIAGNOSIS

Once, it’s safe to start giving treatment, you must first identify what is wrong with the casualty. The process by which you recognise what is wrong is called diagnosis; this will often involve suspicion rather than certainty. Your diagnosis will be a conclusion, probability, on which you should be prepared to act.

Making a diagnosis often requires a thorough physical examination. Factors that will help you include history and clues to any medical condition, and symptoms and signs. Throughout this chapter, the probable history, symptoms and signs of specific illnesses and injuries are grouped under the heading Recognition.

EXTERNAL CLUES

1. Pointers to diabetes

An insulin syringe (which may look like a pen) and/or sugar lumps tell you that the casualty is a

Diabetic.

2. Warning bracelet

This example gives a telephone number for information about the casualty’s medical history.

3. Inhaler

These ”puffer” aerosols are frequently carried by asthmatics and angina sufferers.

4. Medicines

Glyceryl trinitrate is taken for angina, for example; phenobarbitone or phenytoin for epiletsy.

Simpler remedies may give clues—indigestion tablets could indicate a stomach ulcer.